CONTENT WARNINGS: physical violence/assault, kidnapping, racism

I will not go into specific detail on these topics, but they may be mentioned in this review. These themes/instances are unavoidable in the book

Rating: 5/5

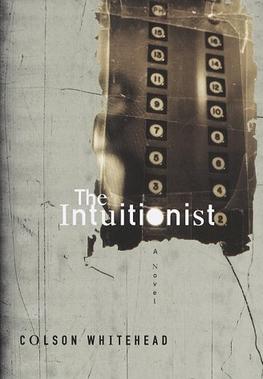

Picking this book up and reading the synopsis of it, I can say that few books have ever felt FURTHER from something I would have enjoyed, or read on my own. A story about politics, elevator inspectors, and a heaping helping of racial allegory? And no, I’m not being metaphorical, and the elevators aren’t some fantasy thing powered by crystalline magic. We’re talking very literal (mostly, anyway) elevators. Actual. People movers. Colson Whitehead’s debut novel The Intuitionist proved my gut reaction of “I would never” wrong in so many ways.

Before I dive into the main character of the story, it’s important to set up a little bit of background for these elevator inspectors. The Department of Elevator Inspectors is made up of two factions: Empiricists and Intuitionists (we love a title drop). Empiricists are the old school, traditional inspectors. They are hands-on and by the book, physically going in and checking every gear and screw manually in their inspections. They are the old guard, and the folks in charge. There has recently been a rise in a new school or inspectors, the Intuitionists. Founded by James Fulton, these inspectors rely on meditation and feeling to do their inspections. Their…Intuitions if you will. Whitehead never calls this magic, nor does anyone in the novel. But, there is certainly an air of magic and mystery into how this is done.

The story’s main character is Lila Mae Watson, an Intuitionist. She is the second black inspector in the history of the department, and the first black woman. Not to mention she’s also enviably good at her job: Lila Mae has the best inspection accuracy rate in the department as a whole. The city and time period are never explicitly stated, but we are led to believe this is a New York-esq metro, with the story taking place in the 1940s. Black, female, and an Intuitionist, there is a target the size of a skyscraper on her back.

Lila Mae is framed for an accident that occurs at one of the buildings she is the Inspectors for, and is thrust into a world of intrigue and politics in order to clear her good name. She seeks refuge amongst the other Intuitionists in the city, and discovers that their founder’s missing journals may hold the key to the next innovation in elevators. This innovation is the so called “Black Box” and is designed to not only be the most perfect elevator, but to take humanity beyond this place, this earth, to another.

Still think this is just about racism in government systems? I sure did until the first mention of “theoretical elevators.”

Lest you think that racism plays second to magical, but not magical, elevators, I can assure you that couldn’t be further from the truth. There is a scene in the novel, where Lila Mae is sent to speak with a woman that The Intuitionists believe could have more information on where the missing journals are. She’s not sent because she’s good at her job, or because she’s the only person around them that hasn’t tried to speak to this woman yet (though that is true). One of the reasons given for why they’re so happy to send her is because, as one of them puts it “you’re both colored.” And boy oh boy let me tell you the absolutely gross feeling that, and the conversation Lila Mae had with the woman, left me with. I had to pause to take a shower.

And that isn’t the only time that I was left feeling that way, but it isn’t a bad thing. Whitehead’s discussion of race and racism is incredibly powerful. Not to spoil anything, but the interactions of Lila Mae with the other black inspector are particularly potent.

One of my favorite things about the work as a whole, outside of the mystery of the (not) magical elevator, is the way in which the story progresses. Elevators are linear things, literally on rails to go only up or down. There is a beautiful dichotomy in the fact the story itself jumps around on the timeline. Sometimes we’re looking at Lila Mae Watson in school, sometimes we’re in the Intuitionist Headquarters. We may be just about to find the next piece of the puzzle, and then we’re whisked away to the past. There was something so enticing about a non-linear story being told about linear objects.

As the story transforms from Lila Mae watson being betrayed and framed as a political tool in a fight for white men scrabbling for power, to the search of an elevator to a higher state of existence, Colson Whitehead’s immaculate storytelling is a steady and driving thing. The Intuitionist is a story about politics, race, the connections between the two, and elevators. Beautiful, literal, elevators. With an ending that left me noth questioning what I just actually happened, and completely understanding how fantastic it was, I was wholly pleased.

Sometimes it’s nice to be reminded of that old adage: don’t judge a book by its cover.